Luxor-Karnak

The Thebes of ancient Egypt - the capital of the Middle and New Kingdoms. The temples and palaces of Luxor and Karnak built on the east bank and the necropolises of the Valley Of The Kings and (mis-named) Valley Of The Queens on the west side as was ancient Egyptian custom - the living on the east where the sun rose, the dead on the west where it set.

The Winter Palace Hotel (front and back) on the east bank of the Nile, built in 1886 by British colonialists and looking the part, including the dapper and oh-so-English Daphne & Roger who we chatted with on the back terrace. Roger looked like one of the original builders of the hotel returning for a top-up of the preservation techniques used by the ancient Egyptians. I think Daphne kept him in the wardrobe and wheeled him out once the sun lost some of its strength. You may find Roger still there propped up in amongst the coathangers if you drop in for a stay.

The hotel is a fantastic Olde-Worldy base for exploring the whole area - the temples of Karnak and Luxor, Colossi of Memnon, Rameses II's Ramesseum memorial temple, Temple of Hatshepsut and the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens. The Hotel faces the Nile and across green, flat farmlands to the desert escarpment where the Valley of the Kings is tucked away.

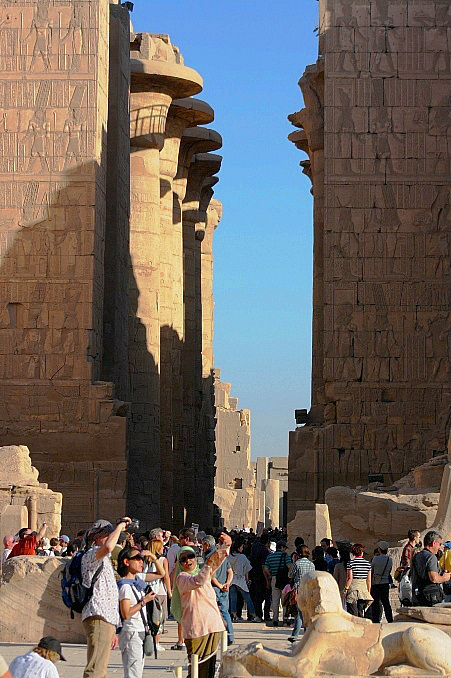

Karnak Temple. The site of futile rituals that celebrated non-existant deities

We wouldn't do that in more enlightend times, would we? At least religion stimulates impressive architecture.

The Karnak Temple complex (above) adjoining Luxor and its temple and connected together by an aqueduct now partially overbuilt. The complex is a vast open-air museum and the largest ancient religious site in the world if we overlook Angkor Wat in Cambodia. In use across the reigns of 30 or so paroahs it has a complexity and diversity not seen in any other ancient Egyptian temples, and has accommodated a range of deities as religious tastes changed.

Colossi of Memnon (below, left). The twin 18 metre statues depict Amenhotep III, 3,400 years old and re-assembled after being destroyed by earthquakes and floods.

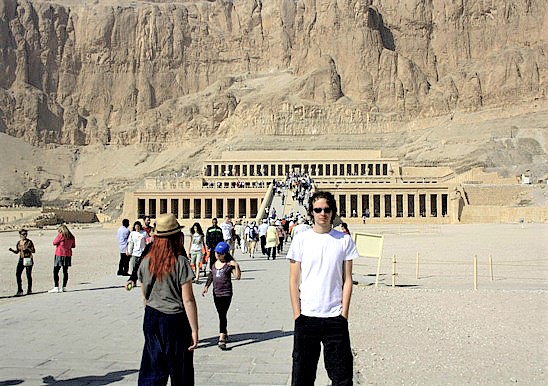

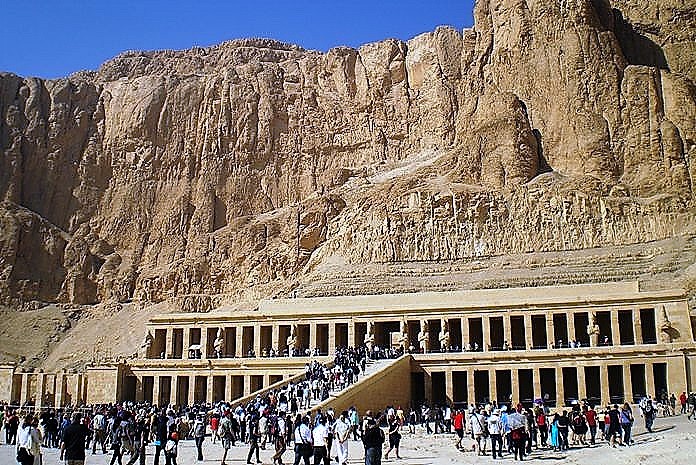

Temple of Hatshepsut, built for one of the few female pharoahs to commemorate her achievements and to serve as a funerary temple for her as well as a sanctuary of the god Amon Ra with some brilliant hieroglyphs with colours still quite vivid.

The Valley of the Kings, while a 20 minute bus ride away, is just over the escarpment behind the Temple. No photography is allowed at the Valley of the Kings - you've got to buy any photos from the various gift shops clustered around the exit. That's really annoying, as were the in-your-face touts trying to extract our money on our way out - the real curse of the pharoahs.

The Valley Of The Kings is 2 valleys - the West Valley and the East Valley which has 59 of the known 63 tombs. The latest discovery was as recent as 2008. Who knows what still remains hidden? Hiding dead pharoahs away in buried tombs was a habit of the 18th to 20th dynasties, well after the pyramid-building ostentation of the mostly 3rd to 4th dynasties of 1,000 years earlier. It's intriguing to ponder the fact that as they placed Ramses II into his tomb in the Valley Of The Kings the pyramids at Giza were already ancient.

The big names of the pyramid craze were the pharoahs Djoser, Sneferu, Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, while Rameses II, Tutankahmen, Seti, Arkenahten and others were put underground in complexes that were covered over and were intended to remain hidden forever. The Valley was in use from the 16th to the 11th century BC. So, by the time of the last internment, the earliest mummy (Tuthmosis I) was already 500 years old. Ramses II was fond of monuments to himself (Abu Simbel being just 1 example) so it's no real surprise that his tomb is the biggest at 120 rooms (and still being excavated).